In my previous post, I mentioned that we’d need to look at some mechanism to throttle the game execution so that we can achieve a consistent speed across hardware of varying speeds, so here I’ll look at how we can achieve this, and why it is important to adopt the method I outline.

As we saw in the code originally posted, the game loop will execute as fast as the computer can execute it. This is far from ideal as it means that the game will run at different speeds on different machines, thereby negating any skill the player may have – after all, it’s far easier to play a slower game, and could be nigh impossible to play on extreme hardware.

There are a number of design patterns that will allow us to throttle the game to a fixed rate that I’ll look at here, and then I’ll conclude by indicating which I’ve selected to use within the Pong implementation.

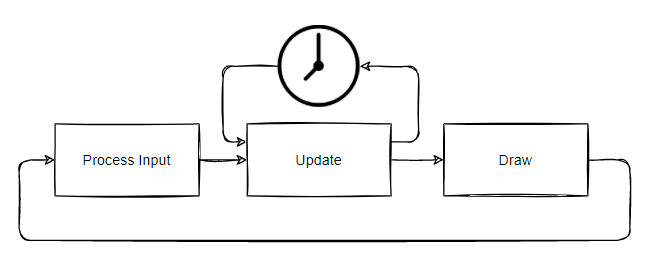

First, let’s recap. The game loop looks like this:

I’ve added in a delay timer at the end of the loop, so we can throttle. The first pattern simply takes a desired frame-time and determines how long the current frame took to execute, then pauses the loop for as long as it needs to. Thus we have the following pseudocode:

frame_rate = 60 # How many frames per second we want to execute

frame_time = 1/frame_rate # How long a frame should take

while True:

frame_start = time.time()

get_input()

update()

display()

while time.time() - frame_start < frame_time:

passSo here, we take a measure of the time at the beginning of the frame, then we simply wait at the end of the frame until the requisite length of time has elapsed.

This works fine for stopping the game running too fast. However, if the game runs too slowly, then we’re stuck. This won’t resolve that issue unless we simplify our game so that the input>update>display cycle is shorter.

The next refinement we can look at is to feed the elapsed time for the previous frame into the update routine. This will allow us to cut back on the amount of processing we do each time should the game begin to slow down. So, for example, if our simulation starts to run behind, we can process the updates in bigger steps, and since we shall be running the simulation as a physics simulation (ie: the ball will be moving according to vector maths rather than fixed pixels) then we can simply scale the vectors in accordance with the elapsed time.

Alas, whilst this will give us smoother gameplay, it can result in unpredictable behaviour within the simulation. Any error within there will likely be magnified and behaviour becomes unpredictable. This probably wouldn’t be so much of an issue for a simple game like our Pong implementation, but for more complex scenarios – especially networked games, this can result in serious headaches for us keeping the various clients in sync.

As a further refinement, we can, instead keep a fixed timestep for the physics update, and simply stagger the rendering cycle so that it takes place on a less frequent basis. This has the advantage that gameplay will be smoothed out, the simulation is predictable and we still can maintain our desired framerate. Thus our gameloop now looks more like this:

As long as our entire loop runs in or around our desired framerate, then gameplay should be smooth and accurate, and more to the point, deterministic.

Our Pong implementation is simple enough that we can likely get away with just the basic gameloop outlined initially. However, I’ll be building with this last iteration so that I have a framework in place for use with other, more complex games in future.

# First, set up the frame timers

t = 0.0

current_time = time.perf_counter()

accumulator = 0.0

while True:

new_time = time.perf_counter()

frame_time = new_time - current_time

current_time = new_time

accumulator += frame_time

# Run update loop

while accumulator >= self.dt:

# Run event pump

for event in pygame.event.get():

if event.type == pygame.KEYDOWN:

if event.key == pygame.K_SPACE:

pygame.event.post(pygame.event.Event(pygame.QUIT))

if event.type == pygame.QUIT:

return

# End event pump

game.update(self, t, dt)

accumulator -= self.dt

t += self.dt

# End update loop

game.render(self)

# End main loop

# End method run

# End class GameSo, this is what the rudimentary game loop looks like at the moment.

Lines 2, 3 and 4 set up the initial state for the timer. Variable t is a simple total elapsed time within the game, accumulator allows us to carry over any ‘spare’ time from the previous frame.

Once we enter the loop proper, we get the start time for the frame, and use that to figure out how much time we had left over from the previous frame. This gets added to the accumulator to determine how long we have available to run for updates.

We then enter the inner ‘update’ loop, and if we ignore the event pump we have in place for exiting the program (this will eventually be cleaned up) we enter our update function, passing in a reference to the game object (for state) along with the total accumulated time and the maximum runtime we have allocated. Once this returns, we reduce the accumulator by our fixed timestep, and increase the elapsed time by the same, and continue looping as long as the accumulator is greater than or equal to a single timestep.

Finally, when we’ve exited the loop, we use the remainder of the last timestep to render the current frame and go back to the top of the loop.

Next time, I’ll start having a look at how game state can be managed within this framework to allow for decoupling of the code into logical blocks.

If everything seems under control, you’re not going fast enough

Mario Andretti